Volkspark Jungfernheide, Berlin-Charlottenburg. Blick auf das Planschbecken. • Architekturmuseum der TU Berlin, 40713

1913-1932 From the German Empire to the Weimar Republic

In the final phase of the German Empire, the desire for social renewal culminated in a reform movement that also influenced open space planning. Straightforwardness and formal rigor were intended to ensure better usability. In the Weimar Republic, open space concepts in the spirit of modernism and expressionism also embodied the search for new forms of expression and possible uses. Despite the ambivalence of the trends, however, the reform-influenced design remained dominant.

Mehr lesen +

1913 Berlin, Bezirk Wedding Schillerpark, Berlin

1913 bdla Foundation of the Association of German Garden Architects

1914 Hamburg Hamburg City Park

1915 München Munich Botanical Garden

1916 Berlin Neukölln Körnerpark in Berlin Neukölln

1917 Lübeck Cemetery of Honor, Lübeck

1918 Hannover Stöcken City Cemetery, Hanover

1919 Berlin Brixplatz

1920 Hamburg Volkspark Altona

1921 Dortmund Main cemetery Dortmund

1922 Kiel Kiel green belt

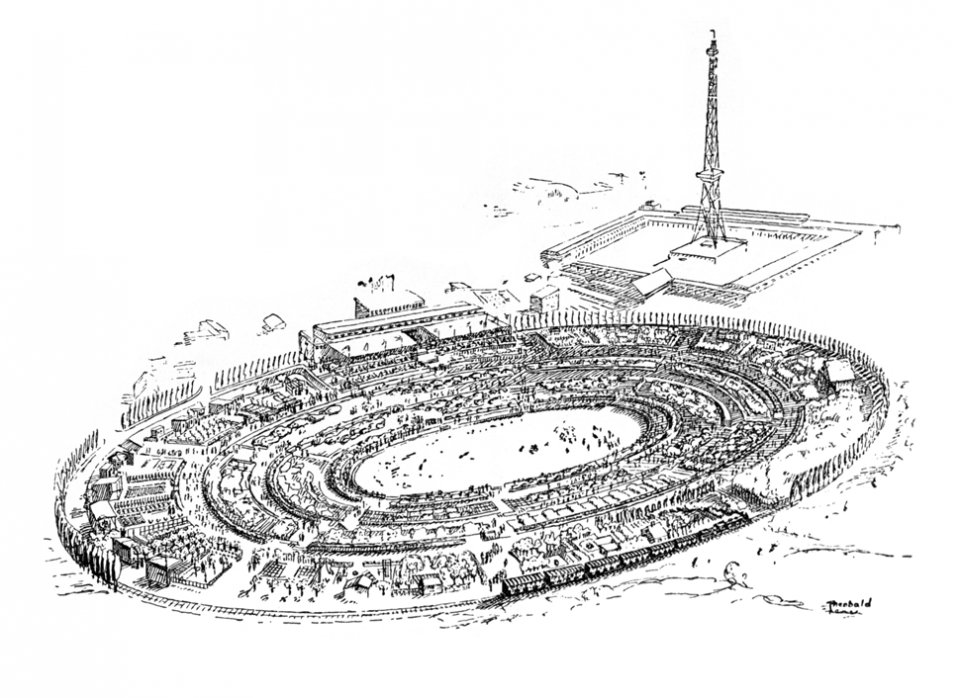

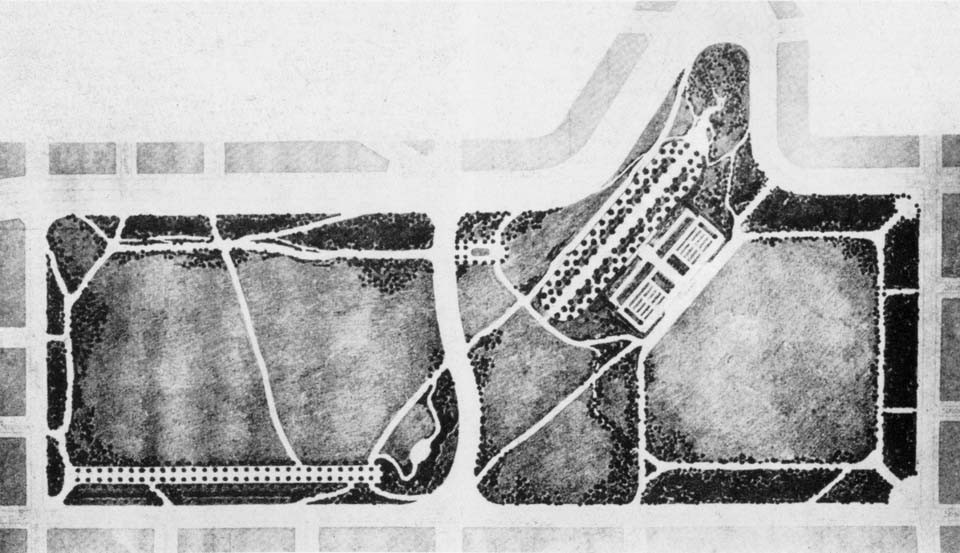

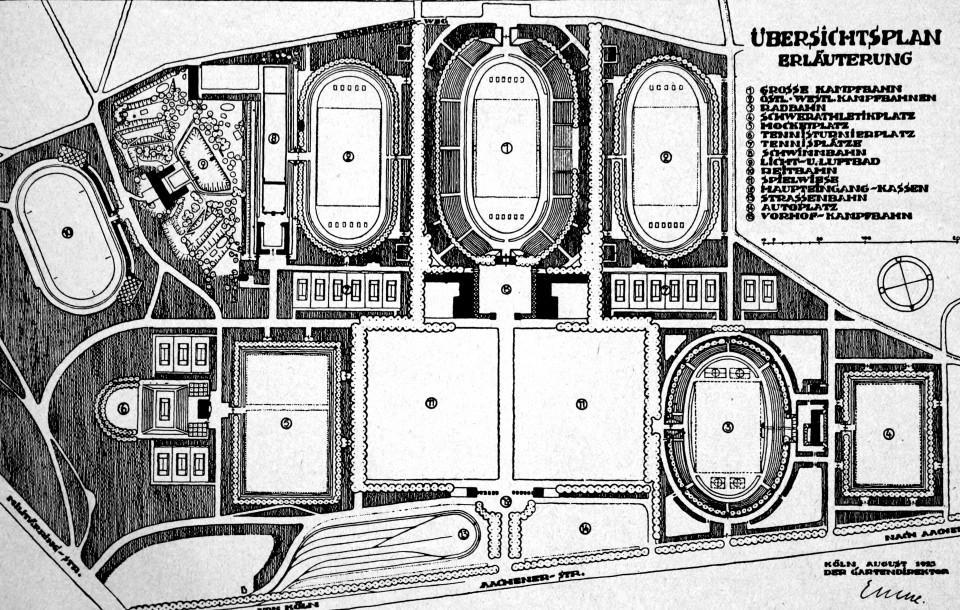

1923 Köln Müngersdorf Sports Park

1924 München The gardens of the Borstei in Munich

1924 bdla Der Deutsche Gartenarchitekt - the newspaper of the BDGA

1925 Dessau-Roßlau Garden of the Masters' Houses in Dessau

1926 Berlin Luisenstädtischer Kanal, Berlin

1927 Berlin Volkspark Jungfernheide Berlin

1928 Frankfurt/M. Römerstadt housing estate, Frankfurt/M.

1929 Essen Great Ruhrland Horticultural Exhibition, GRUGA Essen

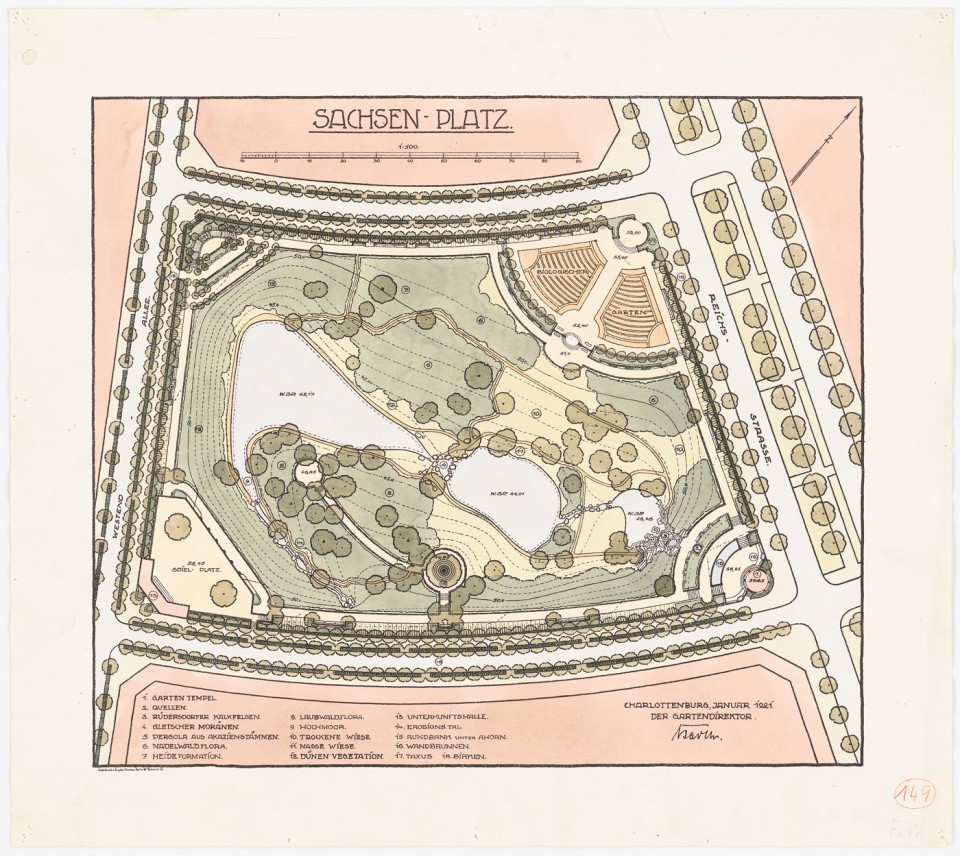

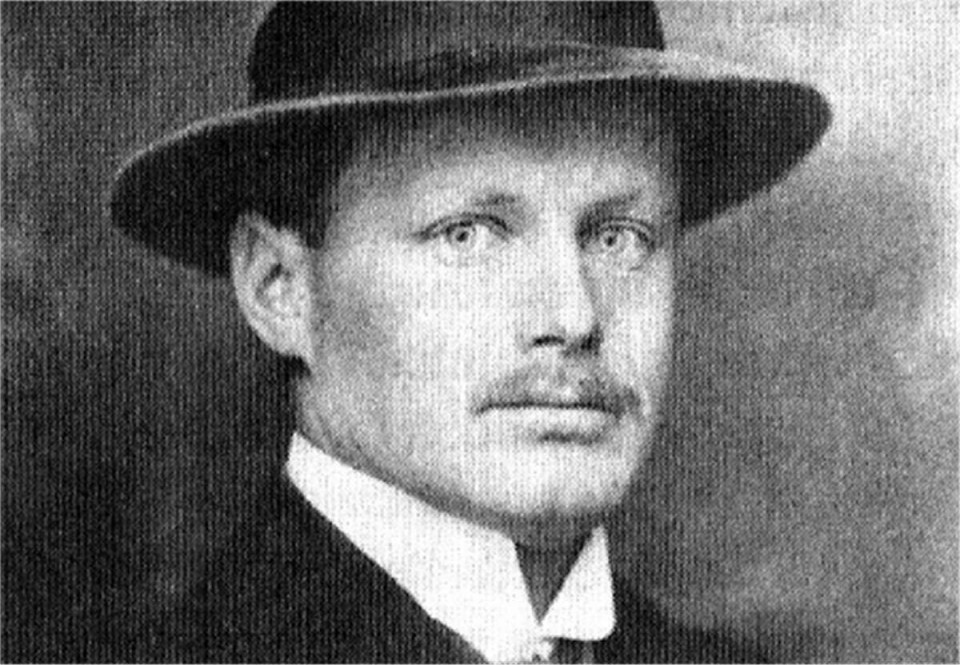

1929 Erwin Barth - Professor of Garden Art in Berlin

1930 Berlin-Zehlendorf Uncle Tom's Hut, Waldsiedlung Zehlendorf

1931 Frankfurt am Main Poelzig Ensemble - Campus Westend