Politically, this era was characterized by the West-East conflict. Socially significant in West Germany were the treatment of open spaces, the consumption of landscape and the change in environmental awareness, which gave rise to approaches to spatial planning and landscape planning as well as the preservation of garden monuments and later also had an impact on object planning. Citizen participation was increasingly practiced in landscape and urban development in the West. Towards the end of the 1980s, a new understanding of landscape architecture as a creative and artistic discipline emerged. In East Germany, the creative will of landscape architects met with limited scope for action in the face of material shortages and strict planning specifications, while on the other hand there was often the opportunity to work beyond planning directives. New collective structures were introduced, e.g. in "offices for urban planning", in which landscape architects worked together with colleagues from urban planning and architecture. Central tasks included housing construction, the creation of parks and memorials as well as facilities for children and young people.

Landscape architecture in the Federal Republic of Germany

By Karl Ludwig

The period from the construction to the fall of the Wall spanned three decades, politically shaped by the West-East conflict and socially by the change in environmental awareness and the break-up of political, moral and behavioral ideas of the post-war period by the student movements. In the 1950s, the profession focused on the reconstruction of destroyed cities and the design of domestic gardens, but in the 1960s its range of topics expanded considerably. The initially hesitant departure into the modern age was encouraged and promoted by looking beyond the national horizon. The consumption and destruction of landscape and nature were now increasingly discussed and criticized, resulting in the establishment of approaches to spatial planning and landscape planning.

The discipline of garden conservation developed from the lamentation of the decay of historic gardens and parks. In terms of education, the higher education landscape was expanded and differentiated into universities and universities of applied sciences. At the end of the discussion, the title of Diplom-Ingenieur/Diplom-Ingenieurin was introduced. At the same time, there was a lively debate about the relationship between the profession and architecture and art - whether it was more artistic in nature or more committed to nature and the environment. It is striking that few other professions have developed so rapidly in such a short space of time. An eloquent expression of this are the numerous professional titles that have been used to date and which, from a professional perspective, have mutated from garden architect in the 1950s to garden and landscape architect in the 1960s to landscape architect since the 1970s. Nevertheless, the debate as to whether the profession should see itself more as a generalist or specialist is by no means over to this day.

Triggered by the economic recession in the mid-1960s and publications such as 'The Silent Spring' or 'The Limits to Growth', the discussion of environmental degradation and ecological planning increasingly became the focus of interest in the 1970s. There was criticism of the state of the city and countryside, and the first theoretical and methodological approaches to planning were developed and applied. The democratic, open society was called for, and the Olympic Park in Munich, completed in 1972 and designed by Günter Grzimek together with the architect Günter Behnisch and the designer Otl Aicher, marked a spectacular highlight of landscape architecture right at the beginning of the 1970s - a unique symbiosis of building and open space, in which architecture and park landscape merge into one another and the park invited free, spontaneous use to 'take possession of the lawn'.

The idea of interdisciplinary cooperation with other professions was added; social sciences such as psychology and sociology were seen as important aspects of open space planning and the involvement and participation of those affected and citizens was practiced with increasing commitment. The aim was to improve the quality of life in cities, pedestrian zones and the living environment.

Landscape and urban development became an essential task of the profession. The Federal Nature Conservation Act passed in 1976 and the associated state laws established nationwide landscape planning, which brought with it numerous new tasks (and jobs) for the profession. When the planning euphoria gave way to planning scepticism in the second half of the 1970s, the ecologically correct garden was propagated in connection with ecology and also found its way into project planning.

Just as the ecological problems remained, the ecological wave also remained virulent at the beginning of the 1980s. Many green roofs and courtyards as well as tenant gardens were created, often together with stakeholders. Garden shows, which were viewed critically and sometimes even questioned, were also an ongoing topic. The first state garden show realized in 1980 led to the creation of new garden shows at state level throughout Germany.

Towards the end of the 1980s, a new interest emerged in landscape architecture in design and artistic issues, which had long been viewed critically in the discipline as voluntaristic and apolitical. This can be seen very clearly in styles such as postmodernism and deconstructivism. The models for this were to be found to an unprecedented extent in the international arena in various metropolises, which became a much-visited Mecca for experts due to their innovative gardens, parks and squares. This was an expression of the increasing internationalization of the profession, but also of an ever-increasing willingness to travel.

Landscape architecture in the GDR

By Dr. Peter Fiebich

On the one hand and on the other: the history of landscape architecture in the GDR in the years between the construction and fall of the Wall is characterized by strong ambivalences. The high demands and wishes of well-trained planners were often offset by limited possibilities in terms of budget and execution. A lack of expertise on the part of functionaries with regard to the concerns of landscape architecture restricted their scope for action; on the other hand, this shadowy existence under the radar also allowed freedoms that other planning disciplines did not have. The implementation of projects that were not anchored in planning "directives" was just as much a part of this as the remarkable development of the specialist field of garden monument conservation based on strong voluntary commitment.

A blanket assessment of landscape architecture in the GDR that is based solely on the final results achieved, regardless of the background, would therefore not do justice to the history. Rather, a differentiated view of individual planning processes, people and the motivations, opportunities and obstacles of their actions is always required.

A fundamental reorganization of the structures of action in planning initially made the tried and tested role of freelance landscape architects obsolete. Some older colleagues were initially granted this privilege, but in the end there was only one freelancer of his kind, Hermann Göritz (1902-1998) from Potsdam. It speaks to the ambivalences mentioned above that Göritz in particular not only created remarkable publications on the use of plants that are still valid today, but also numerous private gardens for prominent "cultural figures" and functionaries. After all, such people were needed.

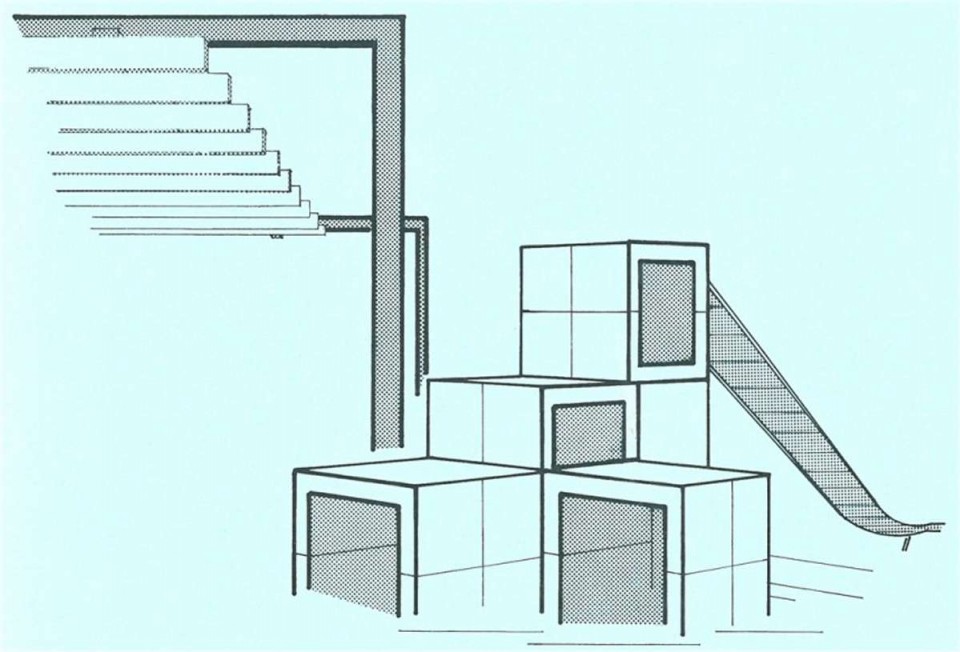

At the same time, large landscaping companies with administration, planning, new construction and maintenance under one roof emerged, whereas the medium-sized companies were destroyed or at best nationalized. The few large companies had a monopoly position and dictated to landscape architects not only a narrowly limited range of materials, but also often the shape of their designs due to the low flexibility of the construction technologies used. In outdoor facilities, as in architecture, exposed aggregate concrete became the predominant material for construction elements. The need for improvisation in turn led to some unconventional solutions.

Landscape architects worked closely with urban planners and architects in the "offices for urban planning" or "offices of the urban architect", in housing construction combines and in the state-owned green space construction companies. The integration into interdisciplinary planning collectives allowed mutual understanding of the professions and synergy effects to mature. In retrospect, contemporary witnesses view this integration quite positively: they were usually able to discuss things on an equal footing. From the end of the 1970s, the offices of the city architects were once again supported by municipal garden departments, which were primarily responsible for organizing the maintenance of public urban green spaces.

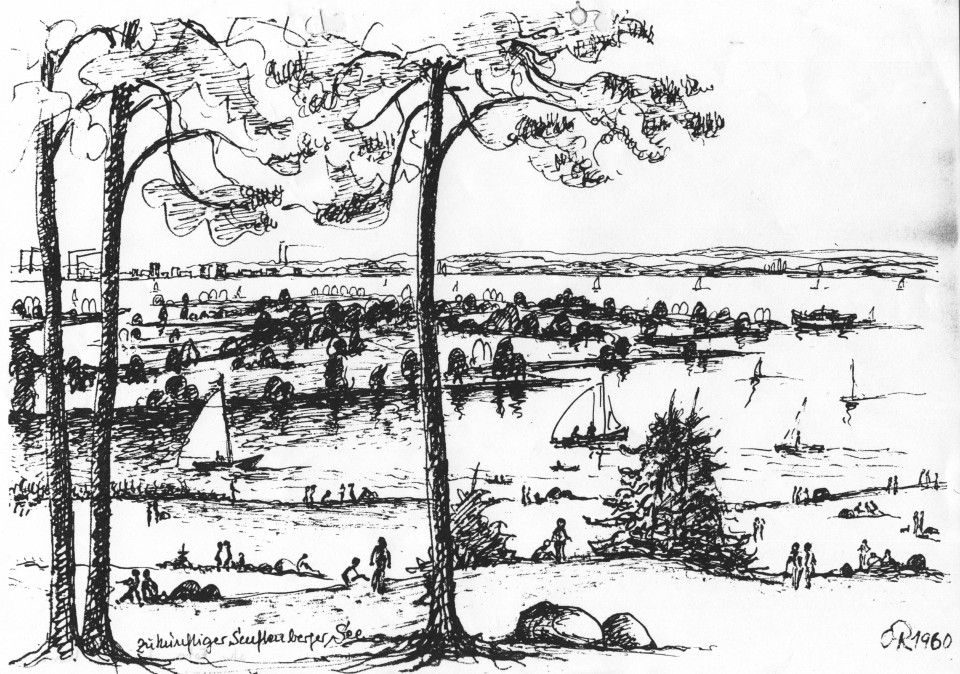

This enabled some progress to be made, particularly at the urban planning level. Extensive statements on open space systems were incorporated into the "general development planning" of large cities. Cities such as Rostock, Cottbus, Dresden and Leipzig emerged with plans that supplemented the open space structure of the existing systems in important places. Large-scale planning, such as the creation of new green links, was of course easier than it is today, as land prices were irrelevant and, if necessary, expropriation was rigorously carried out; the question of ownership was practically irrelevant. This allowed green corridors to be created from which the cities still benefit today, such as the connection between Leipzig's Promenadenring and the park and forest areas of Leipzig's alluvial forest through the "Plastic Garden", which was created from 1980 onwards according to plans by Hans-Jürgen Schwarz and colleagues. The park owes its name to the sculptures that were set up here as part of temporary exhibitions.

Several influential experts who had already trained and worked here before 1945 continued to work in the GDR. In addition to Göritz, these include Walter Funcke (1907-1987), Otto Rindt (1906-1994), Frank-Erich Carl (1904-1994) and Walter Meißner (1914-2000). The perennial plant breeder Karl Foerster (1874-1970) also had an influence on the profession. These older colleagues were soon followed by a young generation trained in the GDR, full of expertise and commitment. They had trained at the Humboldt University in Berlin under Professor Georg Pniower (1896-1960), followed by Reinhold Lingner (1902-1968) and, from 1971, at the TU Dresden, or they came from one of the technical colleges in Dresden-Pillnitz and Erfurt. Names such as Harri Günther (1928-2023), Hubert Matthes (1929-2018) and Helmut Rippl (1925-2022) should be mentioned here as examples, whereby the role of individual personalities increasingly took a back seat to that of collectives. This was also the case in their self-image. When asked about their role in the design and planning process, many contemporary witnesses modestly emphasize the principle of jointly developed solutions.

In line with the centralized structure of the GDR, the Bauakademie der DDR in Berlin was an institution that was directly assigned to the Ministry of Construction and which formulated the guiding principles of future planning and construction. The Bauakademie was also initially responsible for planning selected projects such as the International Horticultural Exhibition (iga) for 1961 in Erfurt under the direction of Reinhold Lingner. In terms of its design and planting, the iga was able to compete with the western garden shows, although the construction of the Berlin Wall in August 1961 clearly limited its appeal. From then on, the iga was held continuously in Erfurt, unlike the changing venues of the western Buga.

The 1960s, the late phase of the Ulbricht era, saw a number of prestigious inner-city projects emerge in the GDR. Although limited to a few "development cities" and mostly located like islands in the urban structure, these modernist ensembles were certainly exemplary in terms of combining landscape architecture with neighboring disciplines. The Park am Fernsehturm with Alexanderplatz in Berlin, Sachsenplatz in Leipzig and Prager Straße in Dresden are examples of a phase in which the word "synthesis" was one of the most important buzzwords in everyday planning and in which urban planners, architects, landscape architects, civil engineers and visual artists came together. It was not uncommon for political messages to be at the heart of such facilities, as in the area surrounding the Karl-Marx-Kopf in Karl-Marx-Stadt, but with their numerous seating areas, water features, flower plantings and space-creating greenery, they also always served people and their everyday recreation. They enjoyed great popularity, far removed from the political impetus.

However, such projects remained an exception, as did the few newly created parks in Eisenhüttenstadt, Neubrandenburg and Leipzig, for example. The landscape architects in the GDR had to struggle with the exterior space of the prefabricated housing estates since the housing construction program proclaimed under Erich Honecker in 1972. While exemplary solutions for residential areas could still be developed in Potsdam's Waldstadt, for example, the possibilities elsewhere often fell short of the wishes and ideas of the planners and users. Often enough, the construction of the outdoor facilities lagged far behind the construction of the housing, so that people had to balance over construction roads to their homes for a long time. The facilities that were finally realized were often enough limited to the minimum of the standards and guidelines laid down in the building academy; there was little room for manoeuvre. The open spaces in the satellite towns were very similar. In their generosity and the planning of flowing spaces according to the principle of the urban landscape, however, they found a characteristic feature that is often only noticeable today, with mature trees, as a special quality. The carefully planted "large greenery" was decisive in shaping this urban landscape. The high presence of sculptures and sculptures in the open spaces close to the apartments should also be emphasized.

Facilities for children became one of the main tasks of landscape architects in the GDR. Schools, kindergartens and crèches, youth clubs, playgrounds and sports facilities were built in large numbers. Another area of activity, which was clearly determined by social policy, was the construction of memorials and "socialist groves of honor". They were built at great expense in terms of materials and costs, even when the severe economic decline was already being felt everywhere. The Marx-Engels Forum in Berlin is one example among many.

Textbooks such as the one by Johann Greiner and Helmut Gelbrich on "Green Spaces in the City" provided a scientific basis for the plans from the Bauakademie. The quality of botanical and dendrological textbooks should also be emphasized. It is no exaggeration to describe the use of plants as a "core competence" of landscape architecture in the GDR. Despite the material deficits, it literally brought outdoor spaces to bloom in many places.

There were no inconsistencies in the profession as there were in the FRG. People consistently spoke of landscape architecture, which was also the name of the specialist journal published by the Association of Architects and the only remaining specialization at the TU Dresden. Despite the country's isolation, the professionals kept themselves informed about international developments, but were mostly dependent on publications and exchanges with the eastern "brother states". Only a few contacts existed across the inner-German border.

A special case here, as in many other respects, was the preservation of garden monuments, which produced a remarkable level of professional maturity in its "niche". In the focal points of the Institute for Monument Preservation and some garden directorates in important parks, but also in the voluntary field in the "park activists" of the Cultural Association of the GDR, there were considerable steps towards the preservation of the garden heritage, which could be thrown into the balance of a common development after 1989.

1 Greiner, Johann; Gelbrich, Helmut: Grünflächen in der Stadt: Grundlagen für die Planung. Grundsätze, Kennwerte, Probleme, Beispiele, Berlin 1976.