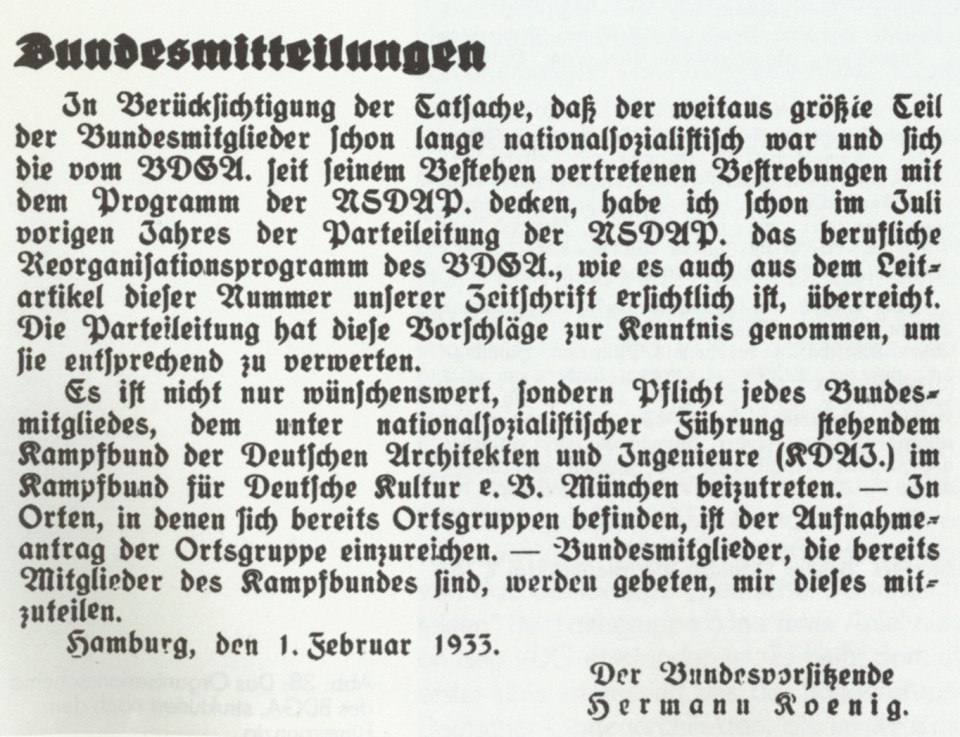

Landscape architecture during the Nazi era was heavily politically charged. The profession experienced severe restrictions and losses due to professional bans and persecution. The attitude of active colleagues ranged from involuntary conformity to approval to active support of the regime. The democratic professional associations were destroyed. The design spectrum was leveled and ideologically controlled. In the field of landscape planning, planning methods emerged that were further developed after the Nazi era.

The development of landscape services of general interest under National Socialism

Even if the years 1933 and 1945 represent clear political caesuras, it makes sense to start from the continuities from the period before and after when considering developments in the history of architecture. To quote the architectural historian Hartmut Frank: "Nazi propaganda did not interrupt the continuity of German building culture, it only destroyed the awareness of this continuity particularly thoroughly." (1985,10)

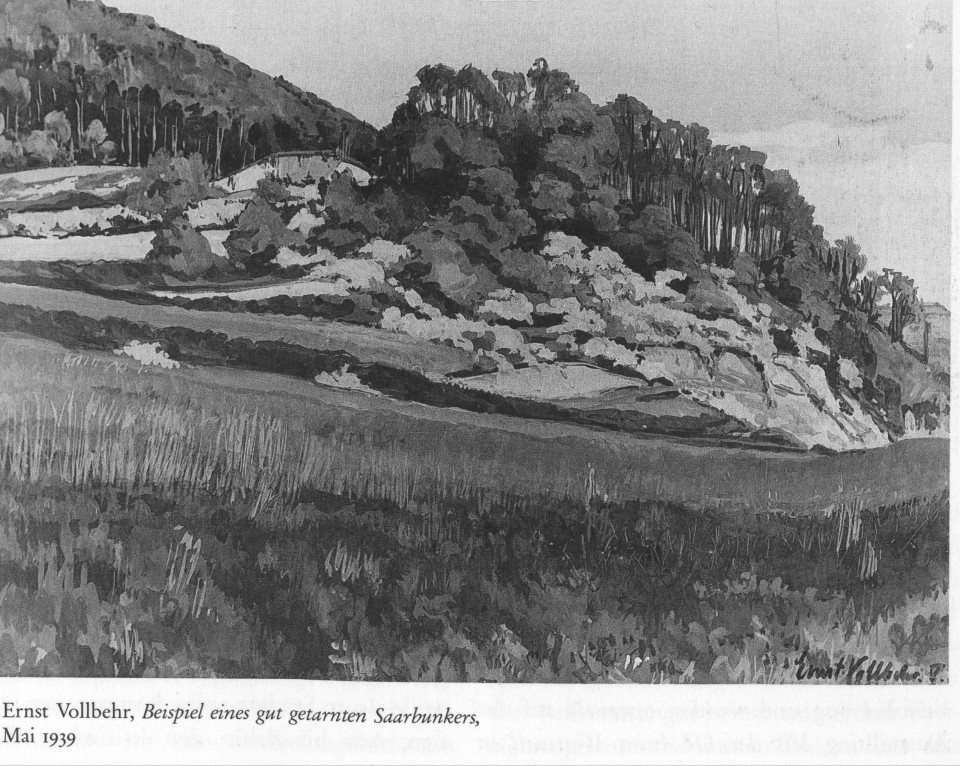

Nevertheless, many programmes and projects realized in the field of landscape architecture between 1933 and 1945 illustrate the specific influence of National Socialist ideology on design issues, the authoritarian understanding of the state and the need for representation of the Nazi dictatorship and the militaristic reorganization of society, which did not exist before and after these 12 years.

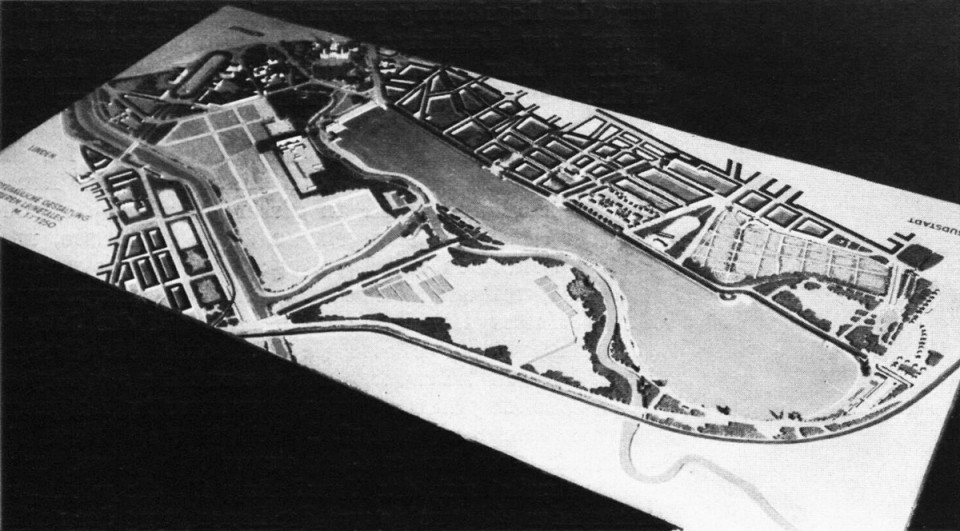

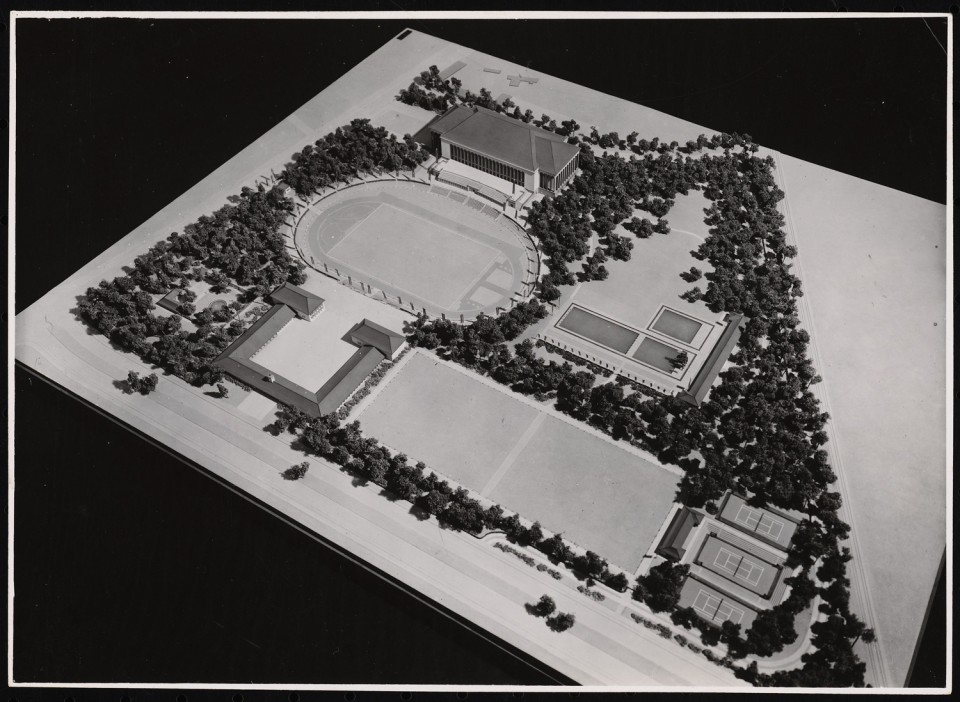

This article is not intended as a summary, but rather as a supplement to the current state of research. It is therefore not intended to deal with prestigious building projects such as the Reichsparteitagsgelände or the Olympic Village, the Great Ruhr Garden Show (Gruga) in Essen in 1938, the Reich Garden Show in Stuttgart in 1939, the KDF-Bad Prora or Tempelhof Airport, or the more or less everyday tasks of home garden design, the creation of factory gardens ("beauty of work") and green spaces in housing estates and on public buildings. Only the decisions taken in the field of landscape conservation, which had a significant impact on post-war development, will be considered in particular.

In the general report "Activities of the landscape designer in the open landscape" by Walter Mertens on the occasion of the 12th International Horticultural Congress in Berlin in 1938, it is stated: "In Germany, the activity of the garden and landscape designer has largely developed into an activity in the landscape." The president of the Reichskammer der bildenden Künste (Reich Chamber of Fine Arts) therefore had the term "landscape" added to the name of the specialist group (1938, 101, 105).

In the Nazi state, the approach was always one that regarded man, technology and nature as an organically interconnected unit that had to be shaped, as Schoenichen programmatically formulated in 1937: "Biological thinking is decisive for the entire racial and population policy of the Third Reich as well as for large areas of our youth and national education and for numerous questions of spatial planning." (1937, 116)

The National Socialist world view of a higher biological order, from which Alwin Seifert and others derived mystified principles of existence such as "essential nature" and "fatefulness", was summed up in 1937 by the chairman of the "German Society for Garden Art" (DGFG) and Berlin city garden director Josef Pertl at the 50th anniversary celebration of the DGfG in Düsseldorf: "National Socialism is an affirmer of nature and its laws. It respects nature and its laws in all its measures in the knowledge that the laws of nature are the strongest in this world and alone are eternal. National Socialism knows that the more a state is in harmony with the laws of nature in its inner structure, the more durable it is." (1937, 214)

The direct connection between the state and the supposed law of nature under National Socialism, which was extended to all areas including technology, formed the political-ideological background for all landscape planning projects initiated during this period. In this construction, "nature" is assigned a mediating function both as a biological-physical habitat and in the form of the cultural product "landscape", which was intended to give the people its "soul" and "essential nature" or to preserve or restore it (Sieferle 1996, 187f.; Klenke 1996, 471).

The NSDAP's goal of comprehensively reshaping Germany, socially, politically and visually, is reflected in the combination of Heimatschutz and Nazi ideology, in which the central premises of landscape design also take their place:

- "Landscape" reflects in its expression "the mental state of its inhabitants" (e.g. Schwarz 1942).

- "Landscape" forms the living space, the homeland, i.e. "the basis of our national and spiritual life", which is expressed "in its ultimate effect" in the concept of "blood and soil" (e.g. in Erxleben 1942).

The importance of the involvement of landscape lawyers in the construction of the Reichsautobahnen at the earliest planning stage, their firm integration into the construction process and the further involvement of engineering biology and plant sociology experts should not be underestimated for the development of today's specialist discipline of landscape planning.

Through this institutionalization, the new field of "landscape design" gained significance far beyond its own specialist circles for the first time. The use of "landscape consultants", who were referred to as "landscape lawyers" from around 1936, established the first binding cooperation between landscape architects and a specialist authority. As key bearers of the National Socialist understanding of technology and nature, the landscape lawyers formed a special group among the engineers of the "Third Reich" in connection with the direct practical implementation of the construction task of "landscape integration".

Central to the history of the discipline is the enforcement of the concept of landscape conservation as a public task: Seifert formulated the demand that "the state must set a good example" in September 1933 on the occasion of the Day for Monument Preservation and Homeland Protection in Kassel "Whoever creates new wastelands with the help of public funds [....], is obliged to reforest them with the native hardwood species appropriate to the location, so that the resulting field hedges can lead to a recovery of the adjacent cultivated steppes." (1933, 1941, 1962)

This claim was implemented in the following years, initially on the Reich highways and from 1940 also in the area of water and energy management. The system of landscape lawyers provided for responsibility for spatially and substantively defined tasks. The combination of soil protection measures, forest conversion, field protection planting and - with the help of engineering biology - near-natural hydraulic engineering, slag heap and mine recultivation, all of which were more or less derived from the landscape design of the Reich motorway construction, crystallized into a comprehensive landscape conservation reform programme.

- The further development of traditional and the development of new fields of activity outside the settlement areas and the associated development of a new professional profile;

- The totality of the planning area: all spatial aspects are subject to planning, landscape design covers sub-areas of this;

- This includes clarification processes of a technical and organizational nature, as well as asserting oneself against the traditional, organizationally, economically and numerically heavier field of road construction, but also against agriculture and forestry, water management, mining, etc.;

- The formulation of an aesthetically and economically sparingly objective design canon with simultaneous monumentalization of the building in a national-racist context;

- Rationalization and technical modernization of planning and construction processes based on national building traditions and potentials;

- Recognition and appreciation of the cultural landscape as a common good, emphasizing its public welfare functions and legalization through nature conservation and landscape design

"The total landscape planning of the cultural and settlement order demands the type and position of a new landscape designer of comprehensive education and responsibility." These were the words of Heinrich Dörr (1937, 12), who later became the landscape conservation officer of the "Reichsstelle für Raumordnung". Dörr formulated this program in his programmatic lecture "Landscape Design and Spatial Planning", held two years later at the 52nd general meeting of the "German Society for Garden Art" (DGG).

On the one hand, the treatise represents a document of spatial planning "blood-and-soil" thinking that can hardly be surpassed in its ethnic-racist penetration; on the other hand, it is one of the earliest concrete formulations of comprehensive landscape planning. In it, Dörr formulated "Ten Commandments of Landscape Design" and raised them to the same level as urban planning. His practical proposals were more concrete than those of Schwenkel, whose book "Grundzüge der Landschaftspflege" (1938) is still strongly anchored in the preservation of local heritage.

The spatial planner called for "general landscape planning" as the basis for all spatial development plans, including the definition of a "landscape network", which was to encompass large areas with "Reichslandschaftszügen" at the level of regional planning (1939, 205ff.). For the landscape designers, Dörr saw that their great hour had come: "biologically trained" and "holistically minded", they were the "born community type among the technicians" (ibid. 203). The text from October 1939, i.e. even before the "landscape rules" formulated for the territories conquered in the East, marked a disciplinary milestone that was also reflected in the discussions of the landscape lawyers.

As landscape consulting on freeways, country roads, waterways, open-cast mines and the RAD had increasingly developed into a public task and conflicts of authority had repeatedly arisen due to the freelance work of landscape lawyers, the proposal for regular employment at provincial level for landscape lawyers, who until then had generally worked on a freelance basis, or for landscape designers to become civil servants, emerged at the beginning of the 1940s.

The discussion about a generalized public task of landscape design independent of nature conservation was initiated in the landscape lawyers' newsletters. Gert Kragh (1911-1982), managing director of the "Hannoversche Provinzialstelle für Naturschutz" and later head of the "Bundesforschungsanstalt für Naturschutz und Landschaftspflege" (Federal Research Institute for Nature Conservation and Landscape Management), for example, expressed a fundamentally positive view of this idea, explaining his efforts to establish civil servant "Provinzial-Bauräte für Landschaftspflege und Gestaltung" (Provincial Building Councils for Landscape Management and Design) and three government building council positions. He saw their powers as nothing more and nothing less than a "landscape police force" and envisioned an administrative structure similar to a road construction authority (1940, 5).

The establishment of regional public bodies, which would commission landscape lawyers, was formulated to great public effect in the proposal by urban planner Erich Kühn (1902-1981) for an organization of landscape conservation, presented at the first working conference of the "Deutscher Heimatbund" in July 1941 at Sternberg Castle and distributed as Appendix 5 in the newsletter of the landscape lawyers of September 1941.

Kühn's detailed proposal ranged from the Reichslandschaftsanwalt (Reich Landscape Advocate), who was to be at the top of the hierarchy, as a Reich office equal to the ministries and "endowed with comprehensive powers", to landscape conservation departments at the governments and landscape conservation offices in the provinces. The management of regionally enclosed landscape areas was to be entrusted to independent landscape designers, the landscape lawyers.

Kühn was expressly concerned with a "generous" and "systematic" expansion of "passive nature conservation" through "active design". The status already achieved in the sphere of activity of the landscape lawyers was to be "legalized by the official appointment of a Reich Landscape Lawyer with a sphere of power encompassing all Reich authorities".

The generally accepted thesis of Gröning

Dörr, Heinrich: Das Grün in der Raumordnung. In: Baum und Strauch in der rheinischen Landschaft. Rheinische Denkmalpflege 9 (1937) H.1, 7-15

Dörr, Heinrich: Landschaftsgestaltung und Raumordnung. In: Gartenkunst 52 (1939) H.10, 199-208

Erxleben, Guido: Naturschutz und Landschaftsgestaltung, Anhang 7 des Rundbriefes der Landschaftsanwälte vom September 1942 im SN 118, 6 S.

Frank, Hartmut: Welche Sprache sprechen Steine. Einführung in: Ders. (Hrsg.) 1985: Faschistische Architekturen, 7-21

Gröning, Gert & Wolschke-Bulmahn, Joachim: Die Liebe zur Landschaft. Teil III. Der Drang nach Osten: Zur Entwicklung der Landespflege im Nationalsozialismus und während des Zweiten Weltkrieges in den „eingegliederten Ostgebieten“ (Arbeiten zur sozialwissenschaftlich orientierten Freiraunplanung Bd. 9). – München 1987

Klenke, Dietmar 1996: Autobahnbau und Naturschutz in Deutschland. Eine Liason von Nationalpolitik, Landschaftspflege und Motorisierungsversion bis zur ökologischen Wende der siebziger Jahre. In: Frese, Matthias; Prinz, Michael: Politische Zäsuren und gesellschaftlicher Wandel im 20. Jahrhundert. Regionale und vergleichende Perspektiven. – Paderborn 1996, 465-498

Körner, Stefan: Theorie und Methodik der Landschaftsplanung, Landschaftsarchitektur und Sozialwissenschaftlichen Freiraumplanung vom Nationalsozialismus bis zur Gegenwart. (Fakultät Architektur Umwelt Gesellschaft der Technischen Universität Berlin (Hrsg.) Schriftenreihe Landschaftsentwicklung und Umweltforschung Nr. 118). – Berlin 2001

Kragh, Gert: Beitrag im Rundbrief der Landschaftsanwälte vom 18.6.1940 im SN 117 Landschaftsanwälte 1940, Bl.5

Kühn, Erich: Landschaftspflege – Eine neue Aufgabe im Dienste der Heimat. In: Heimat und Reich, 1940, H.11, Nachdruck in: Bandholtz und Kühn 1984, 101-104

Kühn, Erich: Vorschlag für eine Organisation der Landschaftspflege (vorgetragen auf der ersten Arbeitstagung des deutschen Heimatbundes in Sternberg), Anhang 5 im Rundbrief vom 8.9.1941 im SN 117 Landschaftsanwälte 1940, Bl.9-11. Zusammenfassend wider gegeben bei Mrass 1970, 19f.

Kühn, Erich: Stadt und Natur. Vorträge, Aufsätze, Dokumente 1932 – 1981. Herausgegeben von Bandholtz, Thomas; Kühn, Lotte. – Hamburg 1984

Mertens, Walter: Tätigkeit des Landschaftsgestalters in der offenen Landschaft. Generalbericht von Walter Mertens, Gartengestalter, Zürich. Erstattet in der Sektion 14 des 12. Internationalen Gartenbau-Kongresses, Berlin 1938. In: Die Gartenkunst 51 (1938) H.10, Beilage, 97-112

Nietfeld, Annette: Reichsautobahn und Landschaftspflege - Landschaftspflege im Nationalsozialismus am Beispiel der Reichsautobahn. (Diplomarbeit TU Berlin, Werkstattberichte des Instituts für Landschaftsökonomie Bd.13). – Berlin 1985

Pertl, Josef: Stadtgartendirektor Josef Pertl, Berlin, anlässlich der Jubiläumstagung in Düsseldorf am 4. Juli 1937 über „Weltanschauung und Gartenkunst“. In: Die Gartenkunst 50 (1937) H.10, 211-216

Runge, Karsten: Die Entwicklung der Landschaftsplanung in ihrer Konstitutionsphase 1935-1973. Dissertation. (Landschaftsentwicklung und Umweltforschung. Schriftenreihe des Fachbereichs Landschaftsentwicklung der TU Berlin Bd. 73). – Berlin 1990

Schoenichen, Walter: Gesetzliche Grundlagen und Grundforderungen der Landschaftspflege . In: Naturschutz 18 (1937), H. 5, 113-117

Schwarz, Max Karl: Nochmals zeitgemässe Gedanken über Garten und Landschaftsgestaltung. In: Nochmals: Zeitgemäße Gedanken über Garten- und Landschaftsgestaltung. In: Gartenbau im Reich 23 (1942) H. 6, 94-95, sowie Anhang 7 des Rundbriefs vom 8.4.1942 im SN 118, 4 S.

Schwenkel, Hans: Grundzüge der Landschaftspflege. (Landschaftsschutz und Landschaftspflege Bd. 2). – Neudamm und Berlin 1938

Seifert, Alwin: Schreiben an Todt vom 18. November 1933 im BArch Lichterfelde (46.01/1487)

Seifert, Alwin: Die Wiedergeburt landschaftsgebundenen Bauens. In: Die Straße 8 (1941) H. 17/18, S. 286-289

Seifert, Alwin: Ein Leben für die Landschaft. – Düsseldorf-Köln 1962

Sieferle, Rolf Peter: Fortschrittsfeinde? Opposition gegen Technik und Industrie von der Romantik bis zur Gegenwart. – München, 1984

Voigt, Annette & Zutz, Axel: Zum Umgang mit dem, was nicht sein darf: Reflexionen über die ,gute Sache’ Naturschutz im Nationalsozialismus. In: Gröning, Gert & Wolschke-Bulmahn, Joachim (Hrsg.): Naturschutz und Demokratie!? Dokumentation der Beiträge zur Veranstaltung der Stiftung Naturschutzgeschichte und des Zentrums für Gartenkunst und Landschaftsarchitektur (CGL) der Leibniz Universität Hannover in Kooperation mit dem Institut für Geschichte und Theorie der Gestaltung (GTG) der Universität der Künste Berlin (CGL-Studies. Schriftenreihe des Zentrums für Gartenkunst und Landschaftsarchitektur der Leibniz Universität Hannover, Band 3). – München 2006, 193-197

Wolschke, Joachim: Landespflege und Nationalsozialismus. ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Freiraumplanung. Diplomarbeit Universität Hannover 1980

Zutz, Axel: Wege grüner Moderne: Praxis und Erfahrung der Landschaftsanwälte des NS-Staates zwischen 1930 und 1960. In: Mäding, Heinrich; Strubelt, Wendelin (Hrsg.): Vom Dritten Reich zur Bundesrepublik. Beiträge einer Tagung zur Geschichte von Raumforschung und Raumplanung. Arbeitsmaterial der Akademie für Raumplanung und Landesforschung Nr.346, Hannover, 2009, 101-148